Maren at the Queen Sirikit Textile Museum’s Symposium in Bangkok & The Amazing History of SE Asia’s Silk Trade

Last November, I had the chance to attend The Queen Sirikit Textile Museum sponsored Symposium “Weaving Royal Traditions Through Time” in Bangkok, Thailand. What a blast! I met textile enthusiasts from all over the world, all of whom were enthusiastic about textiles and eager to share their knowledge and connections. Additionally, we were truly given the royal treatment, being shuttled to museums and private collections in police-escorted, air-conditioned buses, and fed delicious food and drink. As the kickoff event for the Queen’s Museum, this was an event to see!

1. In Bangkok, at private showing of collection of Tilekke & Gibbons Collection textiles – Maren at back left of audience. Photo courtesy of John Ang, Samyama Co., Ltd., Taipei, a fellow conference attendee.

Aside from the pampering and meeting fellow participants (including the renown authors of our most used and treasured books on Laos textiles!), was an incredible 4-day orgy of information on and viewing of SE Asian textiles, with the primary focus on Thailand, but also extending to Indonesia, Laos, Japan, India, Malaysia, and even to England!

I had not grasped, until this symposium, the impact of politics and trade on the location of and production of textiles in SE Asia. I often think of culture and clothing as being static from the point I first see them, but reality is constant change due to trade and imitating others’ work. I also tend to categorize, for comfort and reference, a particular pattern/material/color as belonging to one person/place/time, but the truth is more flexible.

Now, some of the fascinating history:

400+ years ago, the predominant silk textiles in Thailand were saris woven in India delivered via sailing ships. These ships sailed south and east in one season and north and west in the other, following the prevailing trade winds. Due to the long trips, the merchants brought their religious advisors with them. Thus, India exported not only their textiles, but also their religion and culture to Indonesia, Thailand, and surrounding areas. Later, with steamer ships, came the ability to sail against the wind, speeding up trade throughout SE Asia.

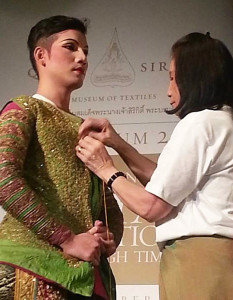

One of the women being dressed for the Khong performance in the brand new gold and red tapestries woven specifically for the dancers. Photo courtesy of John Ang.

Royal court textiles in Siam (now Thailand) were made of saris and shawls worn in the Thai tradition. That is why 7 meters of cloth (sari size) are used each for the traditional Thai skirt and pants. The cloth was greatly valued in the royal courts, and certain fabric was given as payment to those doing service to the King, after which it was required that those textiles were used exclusively in court appearances. Certain patterns and colors were restricted to royal use, and were forbidden to be used by the common people. These restrictions are no longer enforced. (Throughout this time period, local villagers continued to weave textiles, but without the direct support of the royal courts, wove only for themselves for their own clothing and religious purposes.)

A textile preservationist and her assistant at the Queen Sirikit Textile Museum showing one of the Queen’s dresses – made of gold-wrapped silk thread – gorgeous! Photo courtesy of John Ang.

The culture exported from India most predominantly seen in Thailand and other SE Asian countries due to this trade is the royal dance and costume from the Ramayama. Thus, while Thailand is a Buddhist country, the royal dance and theater is based on the battles between Hanuman and Garuda, and other Hindu Gods. I had always wondered why predominantly Buddhist and Muslim countries had such similarity of religious costume and dance expression to India – now I know!

A male dancer being dressed in his Khong performance clothing – the dancers are sewn into their clothing to ensure the textiles stay in place during the athletic performances. Photo courtesy of John Ang.

As a result of this trade, Japan was importing a great deal of the Indian sari fabric from Siam in the 1600’s, leading Japan to believe that the textiles were Siamese in origin. By the mid-1600’s, due to an influx of unwanted missionaries, Japan closed its borders to all but Dutch merchant ships. Thus, the Japanese never learned that the silk saris were made in India, resulting in the name given to them of Sayama, indicating an origin in Siam. The Japanese treasured these textiles, again for portions of royal court dress, and also used the saris to make covers for teapots, to cover boxes holding tea implements, and other culturally important wrappings. The Japanese also tried to duplicate these saris, but, as the Japanese were painting the silk, and the Indians were dying it, the Indian made saris retained their color much longer and so were preferred.

Textile production is also greatly impacted by economic/political decisions. For example, in the 1850s, Siam made a trade agreement to provide rice in exchange for textiles, and from that point on, the people in the center of Siam switched from weaving to solely agriculture. Even now, other than some people who have migrated into the center of Thailand, the area has a distinct lack of textile production. Again, economic drivers trumped cultural norms, though the long-range impact of the shift to solely agricultural production cited here amazes me.

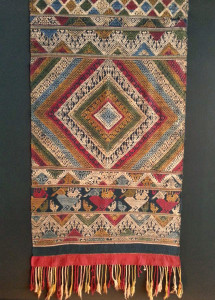

One of the antique Laos textile ends from a shaman cloth which is part of the Tilekke & Gibbons Collection textile collection. Photo courtesy of John Ang.

Also, during much of this time, regions of Laos were under the auspices of Siam or China, paying respective tribute to their King or Emperor. Local rulers paid homage in return for the court clothing and protection of their respective royal patrons. This is yet another example of how fashion and textile motifs and designs spread.

Now, for the more modern influences that caused silk to rise as an economic and cultural phenomenon in Thailand.

When the current Queen Sirikit came to her position, the royal dress of Thailand was western – it had been mandated as such since 1941. When she traveled to NE Thailand in Isan when she was 23, she saw locals wearing skirts of their own weaving, and she commissioned them to weave her some of the stunning textiles. This was the beginning of her ongoing support of weaving in Thailand.

One of Queen Sirikit’s dressed worn on her European tour with the King in the 1960s – stunning cloths representing the best of Thai textile weaving and design. Photo courtesy of John Ang.

When she and King Rama IX toured Europe in 1969, She designed her entire wardrobe, half western and half her own design using traditional Thai clothing styles as an influence, with the assistance of several French and British designers. Her wardrobe became a worldwide sensation, landing her at the top of the best dressed woman list in 1965, the first Asian woman to ever make the list.

Due to the Queen’s efforts, and the ensuing efforts of Jim Thompson, who started the Thai Silk Company in 1960, Thailand is now famous for, to the point of being synonymous with, silk.

Thanks for reading, and for your continued interest in learning more about the people behind the textiles of SE Asia.