The Lao Weavers Visit America

It was a decade old dream come true. Rather than Maren and I visiting our wonderful Lao weaving friends in their village in Laos, we finally “got even” by having them visit us on their first ever trip to America; for weavers Souk and Phout, it was their first time outside of SE Asia. They were able to bring childhood friend Malaithong with them for her translation services and to help facilitate the business and adventure opportunity.

These are three precious friends of ours who we met a decade ago in Xam Tai, Laos when we first started Above the Fray, and their work has been central to the finest quality silks that we offer our customers.

The first week was spent in Santa Fe, where they were welcomed as special guests of the exquisite and selective Santa Fe Folk Art Festival and Market. For two days the jet-lagged weavers attended workshops that introduced them to American business and marketing, and then they sold some phenomenal textiles in the marketplace. Maren and I flew down to assist with the sales and cheer them on. The crowd was dense and receptive, and they did well with sales. Many attendees complemented those Lao weavers, dyers and designers as the highlight of the 150 or more represented artists.

They then spent a week with us here in Eugene – and the weather was perfect. What a blast seeing our world through another’s eyes. A few highlights:

- Watching them take photos in the produce section of Whole Foods – what a selection of greens! The wine department was overwhelming, and just how many kinds of cheese are there?

- Getting to throw a first snowball ever, while enjoying the views at Crater Lake.

- Watching forests glide by the car window for hours. They agree that our life-style here is very tomasat – that is, based on the goodness of being natural. And the roads are so smooth and fast!

- Souksakone asking several times where the rice is grown. (“Why so much grass?”).

- Setting up a full-size Lao loom in our studio, and celebrating its completion with a quick Lao Basi ceremony and a bottle of champagne.

- Finding large, juicy deer walking unabashedly around our Crest Drive neighborhood. Nobody is eating them??

- Eating more meat in a week than they eat in a season – the T-bone with a baked potato was well-received. They agreed they all liked American food – as long as its fresh and home-cooked!

- Roasting the hottest of jalapenos on our bbq grill to gain a bit of “flavor” for the rice.

- Hearing them being impressed with how clean things are – so little litter! (And that is a boastful ethic of ours in this corner of the world!)

- Phout getting her first elevator ride – to the 73rd floor of Seattle’s Columbia Center! Not sure she’ll do that again…

We laughed so much, and we are so grateful for Malaithong’s translation efforts.

On one evening late in the week, as we shared a bottle of wine, Maren mentioned how we felt like we truly had family in Lao. How was it possible for people so far apart to find such a heart-bound friendship?

Malaithong explained that the Lao have a specific word – Seo – to refer to a friend with who you share a deeper connection. And that yes, we were all seo, bonded by our trust and affection.

Malaithong continued. “Here is what I think happened. In the beginning we were of the same family, and then, when all the people were being put onto the Earth, at that moment there was a ver-ry big storm, and a great wind,” and here Malaithong waved her hands in front of her face and made a “whoo-oo-oosh” sound. “Myself, and Souk and Phout blew about and landed in Laos, and you and Josh blew about and landed in America. But we are still of the same family, and now we have found each other.” We laughed and Malaithong shrugged: “That must be what happened.”

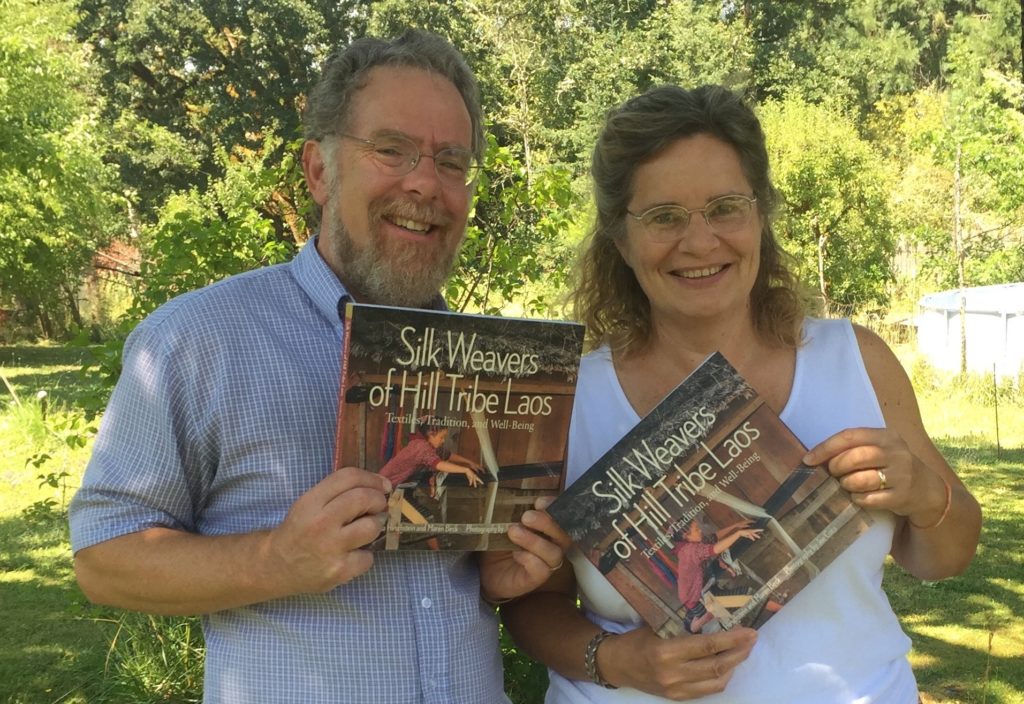

To read more stories and learn about the silk craftwork of these women (and we dedicate a chapter each to both Souk and Phout) and many others, we lure to our new publication: Silk Weavers of Hill Tribe Laos: Textiles, Tradition, and Well-Being (Thrums Book, 2017) by Joshua Hirschstein and Maren Beck, with photos by Joe Coca. You may order an autographed copy at www.hilltribeart.com, or order through Amazon or your favorite bookstore.