The Trials of Southern Laos…

Our families’ March exploration of southern Laos and our return to the now familiar northeast proved a contrast in adventure and learning. We began in the south by flying into Pleiku, Vietnam, and a cursory research of the tribal art in Vietnam’s Central Highlands. A rickety day-long bus brought us cross-border to Laos, where we spent a week exploring Attapeu and Sekong Provinces. The south of Laos proved a challenge to our expectations and patience.

Cows grazing in front of a Soviet ground to air missile used in the Vietnam/American war and behind a fence made in part from bomb casings.

Southern Laos is one of the poorest regions of the world – it is a land still haunted by the atrocities of unexploded ordnance and agent orange from the Vietnam War. Many of its jungle inhabitants, such as the Lavae people, practice slash-and-burn agriculture, which is proving itself unsustainable in the clash of modern technologies and traditional practices. The forests are diminishing, and in an effort to protect the environment and elevate people’s living conditions, the government of Laos is relocating some ethnic groups. The plus side has these people being introduced to sustainable farming techniques, schools, western medical care and the world through television. The negative is that people’s deep cultural roots and traditional arts are being upended, and sometimes forgotten.

A Katu coffin in Laos made in the shape of a Naga (mythical river serpent) is stored under a rice storage shed until needed.

A few large trucks rumble by, hauling rock and sand to a newly dug irrigation canal. Our hired translator, Mr. Si, takes us to several local weavers’ homes. The simple, authentic Alak designs are beautiful, and these textiles are sold in the town’s market and in Laos’ capital, Vientiane, providing Pa’am with needed cash. But the people no longer raise their own cotton; the art of spinning and dying cotton for their traditional clothing is now forgotten. The benefits of Chinese poly-cotton – bright, enduring, washable – have supplanted the ways of previous generations. One has to look back 2-3 generations in the south to consistently find the traditional handspun, naturally-dyed cottons. When something is gained, something is always lost.

Travel in southern Laos is so slow it seems silly. Buses creep along, stopping at every outstretched arm, and average perhaps 20-25 km/hr. What looks on a map to be an hour’s drive inevitably manages to take an entire afternoon. And getting frustrated just makes it hotter. The saying is that the eager Chinese sell the rice seed, the industrious Vietnamese plant it, and the patient Laotians watch it grow. It’s true. However, the Lao pace both has the ability to hypnotize us into a delicious, patient trance as well as toss a brick into our western desire for some sort of business efficiency. Again, something gained, something lost.

We did have some successes in the south. In a Katu village in Sekong Province we had the fortune to find some loin cloths and other textiles with tiny glass beads woven (not embroidered) onto the weft threads to form unique and striking designs. Attapeu had some exquisite aged baskets, and an old man in an unsigned shop in Sekong had some superb Katu and Nghe true cottons and old J’rai rock-bead necklaces. We also discovered a tiny, off-the-track Ta-oy village in Champasak Province where we watched a couple of talented wood-carvers shape protective spirit masks. A woman in that village also brought out a small collection of older boar-tooth adorned protective amulets. We were reminded, once again, that when you slow down, you gain a deeper opportunity to appreciate the skills and talents of the locals and share their time and stories.

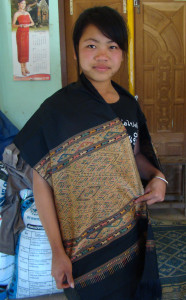

Katu couple in Kadok model a locally-made ceremonial beaded skirt and blouse, loincloth, and shoulder cloth (over a t-shirt).

…And The Calm of the North

The north of Laos weaves a different story. Houaphon, Luang Prabang, and Xieng Khuang Provinces are home to very different people, primarily Tai Daeng, Tai Dam, and Hmong. These ethnic groups, although they also endured the cruelties of the late 20th century, have maintained and even strengthened their cultural art forms. Here we find silk raising, natural-dyes and silk weaving the predominate textile forms, and the millennia-old silk weaving traditions are revered by both the locals and by the “weaving geeks” of the world. In addition, both handspun hemp and cottons can still be found. Perhaps these peoples have maintained their traditional arts because they settled into agricultural ways earlier and developed a tradition of trade with Chinese, Vietnamese, and other Lao neighbors. Markets (and thus market savvy) for their wares and skills have reached beyond their own insulated tribal group for generations.

In the north, poly-cotton thread is readily available and used for some types of textiles (such as high use door-curtains and many skirt borders) but the intricate healing and shaman cloths, and most of the scarves and shawls, are 100% locally-raised, naturally-dyed, hand-woven silk. In weaving villages, young girls are introduced to the intricacies of the loom as they learn to walk. More complex weaving design-work, such as ikat and supplemental warp and weft weaving, are common (and amazing!).

On our 6th visit to our most favorite village, Xam Tai in Houaphon Provice (a Tai Daeng village), we are greeted by master-dyer Souk who pridefully demonstrates the art of creating a broad rainbow of vibrant colors from the jungle’s natural materials and refusing to allow chemical dyes, despite their ease of use, into her work. She continues to hone her dyeing skills, showing off to us on this trip some new subtle color variations she has recently developed. She also beams when she shows us some unique and striking new design-elements she recently created. The textile artists in this region are steeped in tradition, but are also unafraid to develop and enhance the art form. At “Above the Fray” we are most proud of showcasing Souk’s magical masterworks; her textile arts are unmatched.

We were warmly greeted in Ban N—— (showcased in Winter, 2010); the village women crowd around with gleeful smiles and laughs as we handed out copies of the photos we had taken of them and their art on our previous visit. Unfortunately, being March, there are only a handful of healing cloths available. The residents are busily preparing for the rice planting season which will commence with the first rains; once planted, the women will return to their looms to wait out the wet season. “Be sure to call next time,” one village elder says to us. “We will keep things here until you arrive.” The incongruity of their thatched-roofed huts and their modern telecommunications still surprise us. The elders also show off the village’s new cement irrigation and mini-hydro system afforded in part (if not fully) from the cash that the talented weavers bring to the village. Markets for their talent and wares, they’ve discovered, exist well outside their narrow valley.

We also found that Muang Vaen (showcased in Spring, 2008) has grown over the last two years. A dozen larger new homes have sprouted up, and the 30 kilometer dirt road to this outpost was recently re-graded. Motorcycles (110 cc models are the preferred transport for all up and coming families in Laos) zip about, and the small local stores seem top-heavy with Pepsi, shampoos, and television sets. While we in the West may shudder at the advent of such choices, it is an indication of a more stable economy and a more educated, healthier population. They too want their children to thrive in a rapidly modernizing world.