Maren recently returned from a month-long solo trip through the hilltribe regions of NW Vietnam and NE Laos, staying with many of the friends and “business contacts” we have developed over the years. If there’s one thing we’ve learned: hilltribe cultures value friendship as centrally as they value family and community. As the following excerpt from her weekly “home-report” reveals, kindness and company are the greatest assets anyone can share.

March 3: I’m in Vietnam, in Sapa, having arrived this morning by train. My friend and “sister-in-all-but-blood” Vandara from Luang Prabang, Laos, has come with me to see how Sapa does selling in their market, and how the materials are made and distributed. She runs the guest house we stay in in Luang Prabang, has her fingers in an overwhelming number of projects supporting traditional Laos materials production, and is on several government task forces to help the Lao people find ways to ensure healthy, self-supporting, traditional activities. With her, work and pleasure are one and the same. Wonderful woman, and a force of nature.

But to fill you in on the last week: We did manage to get to Phonsavan (in Xieng Khuang Province, NE Laos), but had a couple of mishaps. The road from Xam Neua to Phonsavan (8 hours) was closed for several hours due to a rainy spell the previous night that had turned a section of the road into a slip-and-slide. A bus slid off the road into a ditch, and no other vehicle could get by. Everyone was OK, but it took a huge crane/tow truck to pull it out of the ditch, with chains looped around nearby trees to stabilize the tow truck while it pulled. Once the bus was out of the ditch, the next bus to come down the road did the same thing. A long day at that bend in the road. Our driver got out of the car, along with the rest of us watching, and proceeded to shovel drier mud onto the road to provide some traction. With the help of 6 young men pushing, we were able to make it around the curve, barely missing the ditch ourselves. Two hours later we stopped for lunch, and, looking down, I saw there was a legitimate reason for my squishy-feeling foot; the squish was coming from a sandal full of blood. Apparently I picked up a leach while observing the bus being pulled out of the ditch! I didn’t feel a thing until the squish. My first leach in all these years of travel! My friend Mai (our translator and good friend from Xam Neua) was quite concerned that the leach had dropped off in the van, but we never found it.

The bus in the ditch from the slippery road, and the towtruck men in the trees bracing the truck for pulling on the bus.

Phonsavan was great – had dinner with Mai at her friend’s house. Spent the next day in Napia gathering more aluminum articles, spoons, bracelets, etc., made out of pieces of American bombs recovered from the soil after we dropped the bombs on the Laos during the “Secret War” portion of the Vietnam “conflict.” (See the next article for details on the impact of the war.) On a cheerful note, I spent several hundred dollars on a family in Napia who make spoons, bracelets, bottle openers, and other items from the leftover aluminum. The money we make selling these items will all be donated to MAG (Mines Advisory Group) to clear unexploded ordnance.

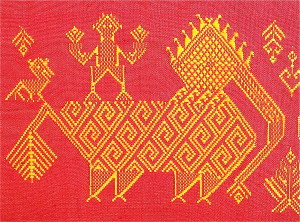

I also went to a local Tai Dam village where I found skeins of handspun, naturally dyed cotton and lengths of woven cotton, and distributed the dozens of photos we took there last year. The women were really pleased to see me again and were more than eager to sell their materials.

Then my guide, Khen, who was our family’s guide last summer, took me as his “date” to a friend’s wedding – a very strange event. The men and women danced in a group, rotating slowly counterclockwise, while the women shifted their hands – first left facing themselves and right facing their partner with fingers together in Thai-type poses, then, 4 steps later, reversing the order. The group vibrated up and down about 2 inches with each step, and a very slow-motion dance ensued, all to deafening karaoke music. The crew was quite inebriated, of course, as is required at a Lao wedding. Over 150 people were there, complete with food, beer, lao-lao, dancing, dogs, children, and chickens.

Off to Luang Prabang (Laos’ second largest city), where our friend Vandara was busy with a class of 17-25 year old local women learning embroidery techniques from a Hong Kong group, for whom Vandara was providing translation services. Vandara was exhausted from the 6-day seminar, and I only saw her for a couple of minutes each day. I ended up spending a lot of time with Marie, a French woman who also adores Vandara, wandering around town to visit our usual contacts. We ate dinner at different places each night, accompanied by a Dutch woman who, with her partner, were creating a butterfly and orchid garden near Vandara’s second guest house that would include a bakery and cafe. The most interesting westerners end up populating Asia! The three of us had a blast together though, spending each dinner in hysterics.

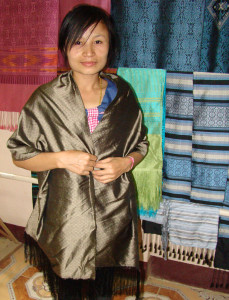

Our source for some of our simple handwoven silk scarves picked me up at my guest house and took me to her house where I perused high piles of silk, choosing the colors and styles that I think will work – who knows if I’m right – and was fed, watered, and returned to my guest house with all of my chosen textiles left behind at her house, with a pile of her friends/relatives labeling our choices to meet customs requirements. The next day they were delivered to the guest house (even though I hadn’t paid for them yet) as I only saw the scarves on Saturday, and the banks were closed until Monday. Talk about trust!

Our talented wood hanger carver carefully cuts the outline of the cragon hanger on his homemade jigsaw – no finger guards!

Monday, the man who carves the wooden hangers we carry picked me up at my guest house on his motorcycle, and he took me to his home where his wife had lunch waiting. I took pictures of him carving the hangers to have available for our customers, made my final selection of hangers – most made of rosewood – and then he drove me back to my guest house in his tuk-tuk so the hangers could come with us. He was so sweet, spoke excellent English, and we shared philosophies on child rearing on the trip back. Zall and Ari – he is as conservative as your parents are – even more, given Laos culture, regarding the freedoms allowed his children. So there! We’re not the worst parents in the world!

I managed to get all of our items labeled, packed in bags and boxes, and put in a bus to be sent to our shipper in Vientiane – he e-mailed me that he received everything in good shape, and our shipment is ready to go as soon as I pay him. I love the trust relationships here.

Tomorrow Vandara and I will peruse the Saturday market here in Sapa, then take motorcycles with Tea to to her mother’s house where her family has an assortment of handwoven, naturally dyed, handmade Hmong bags ready for me. Sunday we go to another market several hours away, and then Monday, to my Red Dzao friend Ta May’s village, to visit some other friends and pick up the carved wooden dolls made in that village by a really nice, cute, talented elder from whom we have ordered dolls before. They are all hand-carved, with moving limbs, and wearing traditional clothing made from real handwoven, hand embroidered and dyed with indigo and other natural dyes. Lovely.

Our good friends Tea (Sho’s sister), and Ta May in their traditional Black Hmong and Red Dzao clothing.

Monday night, the train back to Hanoi, then Vandara and I will spend the day seeing some business contacts and friends in Hanoi, then she goes back to Laos. After she leaves, I get to spend the remaining time in Laos doing the joyous work of labeling, creating invoice and packing lists, packing, and getting the final items off to our Vietnam shipper. This is when I really miss Josh…. I am starting to look forward to getting back home.