A young girl, perhaps 6 years old, sits upright on the loom’s bench in the shade of her family’s home; you can see the creases of concentration on her brow as she pushes the shuttle through the shed that she had carefully lifted with her weaving sword. Her grandmother sits on a stool next to the girl’s loom and, although busy with her own lap-bound textile project, she occasionally offers a few soft words to the girl. It is the first week of the girl’s official weaving lessons, and she does look serious sitting at her own loom, her silk project stretched across the warp and weft threads in front of her.

This seven-year old in Ban Tao, Laos sits under her home with her grandmother and weaves for an hour each day after school

Granted, the young artist-in-training has for years been watching her elders daily at the loom creating the textiles that both transmit the knowledge and mores of their culture and support the economy of the community. And in this village – Xam Tai, Laos – about 90% of the women weave.

Occasionally, Maren and I share photos of young weavers, and often – and not inappropriately – there are queries about the pressures and expectations on the young workers. Indeed, are they being exploited? It’s a valid question, and the world is rife with examples of unhealthy child-labor situations.

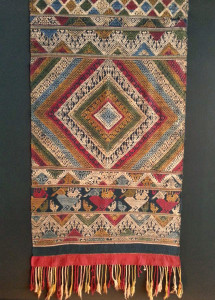

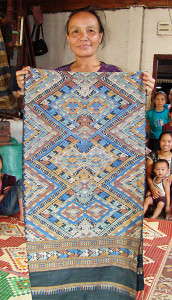

Nine-year-old Mai Chom of Xam Tai, Laos hold up a “sample-sized” silk, affectionately called a “love token.”

Children who live in traditional, rural communities are usually expected to participate in the essential daily tasks: sweeping the compound, caring for the farm animals and the vegetable garden, assisting with the maintenance, planting and harvesting of the fields, caring for younger siblings and the very aged, helping with meals and laundry. All these tasks and more are essential components of how an indigenous healthy community a) facilitates the daily tasks of living, b) teaches to the young the myriad of practical skills necessary for a healthy community, c) transmits the communities’ ancestral knowledge and mores to the next generation, and c) generates an economic benefit. Youth itself, starting at school-age, offers little excuse for a demonstrated lack of responsibility or “pulling of one’s own weight.”

In Xam Tai, Laos (cultural home to some of the world’s finest naturally-dyed silk art), almost all youth attend public school from age 6 to 16 (usually 9-11 AM and 1-3 PM, 5 days a week). After school, each is then expected to assist with essential household and community tasks for 2-3 hours. The boys are generally expected to join the men in fieldwork; the girls typically join the women at the loom. Some girls in Xam Tai choose not to dedicate their time to the weaving task – not everyone has the patience or skills – and other household or field tasks offer an alternate contribution. Also, during rice-planting and harvest time, all members of the community assist in the essential fieldwork.

In a modern, wealthy society, such task development for youth often gets channeled into the development of specific talents such as playing the piano, pitching a baseball, painting a picture, acting on-stage, or practicing ballet. The hours of work/play spent in such hobbies and extra-curricular activities certainly contributes to the individual’s development, and also has an impact on the broader community (albeit an impact that rarely plays to immediate needs). In fact, these activities are my culture’s means of transmitting cultural knowledge and mores.

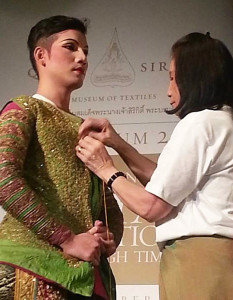

15 year old Ta of Meung Kuan, Laos, displays a ceremonial textile that she designed and wove of naturally-dyed silk. She weaves for about 3 hours a day after school.

In traditional cultures, one’s time and participation tend to be closely tied to pragmatic considerations (especially if, as in rural Laos, subsistence living is in living memory). The pervading norm that “we must all contribute so we can all make it” becomes a dominant cultural voice, and a youth’s participation in supporting the larger community becomes the key vehicle for that youth’s maturation. Whereas some cultures might reward individual expression and “striking out on one’s own,” (indeed, even egotism), other cultures – especially small, traditional groups – hold more strongly to the ethic that the unity of the group and an ethic of “belonging-ness” supersedes the promotion of the individual. The cross-generational needs of the family and the economic and spiritual health of the community are priority.

This photo was taken on this 6-year-olds first official day of sitting at her own loom. Her grandmother sat at her side instructing her.

Pride in being a contributor – a “grown-up” – is clearly seen on the faces of the young weavers (as well as their parents and grandparents). Finally – mature enough to participate! As parents we saw that pride in 3-year-old Ari as he poured in the pre-measured washing powder at a laundry task, and as 7-year-old Zall joined in to help stack the firewood. The individual spirit lifts when we contribute to “real-world” tasks – when we’re a member of the “getting-it-done team” – and this pursuit of the greater good is a young person’s path to gain respect and skills.