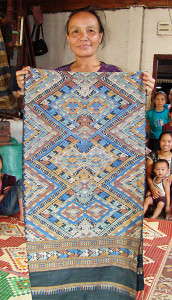

Souksakone Khakampanh: Master Dyer & Weaver

If Above the Fray were to select a single artist most emblematic of the modern talent and skill of the hilltribe weavers, or if we had to choose a single textile expert to represent, Souksakone Khakampanh would be our choice. Hands down.

| Souk (rhymes with “book”) lives in Xam Tai, Laos, a village on the Xam River surrounded by the jungle hills of SE Houaphon Province. The village of several hundred people is 5 hours by vehicle from the provincial capital of Xam Neua, a drive that winds across the steep jungle ridges of the remote Nam Xam National Protected Area. Xam Tai, however, is anything but desolate and backward. The internationally-acclaimed silk weavers, designers, and dyers of this district – Xam Tai and its surrounding hill villages – are legendary for their skills at raising, dyeing and weaving silk into intricate, complex forms. The locals, primarily of the Tai Daeng ethnic group, are industrious (every home seems to have several floor looms), healthy (a new hospital clinic just opened), wireless (everyone has a cheap cell phone), educated (district secondary schools are located here), and, most obviously, proud of their community’s ancient and renown talent and reputation.

When we visited Xam Tai in 2007, Souk was introduced to us by Mai, our translator from Xam Neua who just happened to have grown up as Souk’s best friend (needless to say, that worked out well for us!); we brought home several of her textiles for our own personal use that year. In 2008 we returned, this time with business plans, and Souk dedicated an afternoon to teach us about how the traditional natural dyes are made. It seems that in addition to being an expert weaver, Souk is a master dyer who can coax subtle tones and rich hues from the traditional natural dyeing materials. [No one in Xam Tai uses commercial dyes, despite their efficiency, brightness and longevity.] She showed us lac, a bug excretion found on a certain tree that is exuded to encase and protect the bugs’ eggs, that had been collected for the required reds. Sappan wood creates a range of pink to violet. The haem vine creates one hue of yellow, mango tree bark another. Cooking techniques and additives can additionally shape colors to have certain tones. Mordants, such as lye from rice ash or slaked lime, are then skillfully added to set colors onto the material. Souk’s created colors are treasured as much locally as by dyers around the world. [More about the dyeing process, as well as a bibliography of resources, can be found at www.hilltribeart.com.]

|

Souk is modest and beautiful; she displays a calm exterior and easy smile that hides a whirlwind of creative talent and “get-it-done” energy. Her home is base to a hundred projects. A rainbow of freshly dyed silk skeins, from bright yellow to murky green to rich maroon, drape over a bamboo pole. Vats of deep colors bubble and froth on a series of small focused fires – bundles of silk bob in each differently colored “soup.” Two floor looms, one in pieces, sit beneath a roofed arbor in front of her home; a rich blue is strung on the warp, and the weft threads are beginning a stunning green and red pattern of naga – the mythical river-serpent motif – that will stretch across the textile. Chickens, children, drying corn and a small tractor engine share the shade. Friends, as well as a couple aunts and cousins, upon hearing that “falang” are in town, drop by eager to show their goods as well; Souk makes time and room for everyone.

Souk, who does not speak English, shared her personal story through Mai. She was born and raised in the center of the Xam Tai weaving community; she began her training with her mother, first learning basic weaving at age 7, then dyeing techniques at 10. Her family, like many households in the area, had looms set up under the thatched-roof bamboo homes; it was assumed that girls would participate in the traditional art both because of its cultural importance – and Xam Tai is particularly renown for its complex Shamans’ ceremonial blankets – and because of the textiles’ trade value. Soon she had learned all she could from her mother about dyeing, and began experimenting with her own dyes and color combinations. She has since taught others in her village her new dyeing techniques, and has taught a multitude of dyeing classes in Laos’ capital, Vientiane. She has even been invited to go to Japan to teach dyeing!

These days Souk focuses on dyeing and design-work, and she directs a cadre of 70 weavers in regional villages who can meet her highest-quality expectations – a single ceremonial wedding blanket takes 4 months to weave. When designing the motifs and patterns, Souk reverently adheres to her Tai Daeng traditions, but she also has the confidence to create some subtle new design forms. She explains to us that while the traditions are important, each generation needs to make an impact on the art. She now finds herself to be one of the communities’ leaders and works tirelessly to maintain the ancient artistic traditions, and yet all the while developing new forms, dyes and markets.

Souk always gives us 2-3 hours to sort through her several stacks of tidily folded silks – it is tough to choose from the range of designs and colors. Once she disappeared for a half hour only to return with and big grin and bowls of steaming frog soup. At the end of our afternoon, we negotiate a little – but she smiles and budges on pricing only an inch; we all know that she can sell her textiles, sight unseen, through distributors in Laos’ capital at her asking price (indeed, we saw some of her pieces in some up-scale silk shops there). She knows the value of her art. After all, she knows the people who raised and spun the silk; she knows the time it takes to find and process the raw materials that make each threads’ color; she knows the hours it takes to create each pieces’ unique design; she knows the effort and precision involved in the months of Koh weaving (see the next article). She knows she offers the very finest, and, smiling proudly, she readily accepts that compliment.