Both Laos and Vietnam closed their borders to visitors in March, a few days after Maren returned to the US from Hanoi during her Spring business visit. Now, nine months later, the borders still remain closed, much to the apparent health benefit of the local population. To date, Vietnam (pop. 95 million) has had a total of 1,381 cases with 35 deaths; Laos (pop. 7 million) reports 41 cases and no deaths. [It makes one wonder if the people in the region may have some degree of immunity to this particular virus.]

That is not to say that the lives of our friends and many others in the region haven’t been sharply affected. With international tourism shut down, those who provide guiding, transportation, accommodation, and food services for the annual 18 million international visitors to Vietnam and 4.5 million visitors to Laos (2019 numbers) have been largely unemployed and reliant on other means of “getting by.”

Somchanh, in the foreground, carves a textile hanger.. HIs brother-in-law, the other carver, helps with the business when the tourist market is busy.

Somchahn, a talented woodcarver in Luang Prabang, Laos who has supplied Above the Fray with wood hangers and other carvings for over 10 years, reports that he has no sales, and the famed night market in Luang Prabang is closed. His recent investment into being a guide and translator also has been halted. He says he is fortunate that his wife’s family lives with him, and he has been harvesting food and doing other odd jobs as he awaits the return of his livelihood. Our pre-payment for his wood-carvings, which we will pick up when we next return, was greatly appreciated.

A photo from 2005 – that is 9-yea-old Zall, 12-year-old Ari, and 18-year-old Sho on the first day we met. We hired Sho to be our guide for the day, and our friendship with her (and later, her family) has been central to our relationship with Vietnam for 15 years.

Sho, our first Hmong guide in Vietnam who now lives with her husband (a hotelier) and children in Luang Prabang, and who owns a boutique textile store, reports that there are very few sales. She has closed her second shop and, like many, is relying on a few sales to the local population. She says she feels fortunate to be open t all as 75% of Luang Prabang’s inhabitants rely on tourism for their living, and so most of the hotels, restaurants, and shops have closed. Everyone is well, she smiles, but everyone is ready for a return to “the normal.”

Thi, our liaison to northern Vietnam and a dear friend for many years, has had her life turned upside down by the pandemic, but she and her family are adapting and faring well.

Thi, Sho’s sister who lives in Hau Thao in northern Vietnam (where Sho grew up), and who has also been our guide, translator, host, “textile advisor,” and dear friend for many years, also smiles when she says things are well – and by that she means everyone in the family is healthy and safe. The new 2019 expansion of her guesthouse sits idle, and the few tourists visiting the region – all Vietnamese traveling in-country – are not very interested in the cultural experience of a Hmong homestay or learning how traditional textiles are dyed, batik’d, embroidered, and woven. Trang, her husband, is still making and selling jewelry (which Above the Fray highlights!) to the local Hmong population, as he has for 25 years. Her family’s garden, she says, is large and flourishing this year.

Trang embosses a set of earrings for the local Black Hmong community in his workshop at his home in Hau Thao, Vietnam.

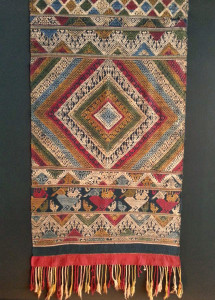

Our dear friends in Houaphon Province in NE Laos – Souksakone, Phout, Malaithong, Lun and Bounkeo, Nang Tiip, and many others – where we have invested much of our time (and is the topic of our book, “Silk Weavers of Hill Tribe Laos”), are probably the least affected. Of course, the markets have dried up for the types of textiles that tourists tend to purchase. However, the tradition in Laos is for Lao women to wear a Lao-style sinh (skirt), so currently more weavers are creating sinh to sell to the the Lao people. While this market is more limited, it allows the wheels of the silk-weaving economy to continue to turn. Worms are being harvested, silk is being spun, the looms are clattering away. Mai says that many weavers are learning how to market online to the Lao-speaking customer.

However, there are deeper currents of change in this part of the world beyond the impact of the pandemic as the rural communities modernize at an extraordinarily rapid pace. Many of the weavers, especially those living in small villages, will be facing strong winds of socio-economic and cultural change as the tourist industry, and development in general, rebounds.

We note that many of our friends in Laos and Vietnam are not far removed from times of austerity or transition. Most of the people with whom we have contact still have close ties, if not current outright responsibilities, to extended families and maintaining a family farm. No one voices concerns about going hungry or being abandoned, especially in the rural areas, which have a recent history of being quite self-sufficient, thank you very much. (As one friend notes: “Hey – at least this time there are no bombs are falling from the sky…”)

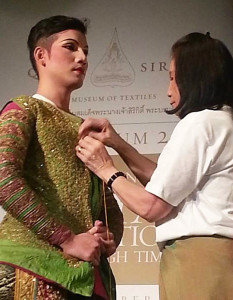

The weavers are still weaving during the pandemic, but the markets have changed. Here Maren peers over the shoulder of a silk weaver to see the new creation.

While people are aware of the risks of the coronavirus, no one who we have talked with knows anyone who has had Covid-9. They understand the risks of the virus and listen carefully to government instructions and information, but the truth is that our contacts in Vietnam and Laos are far more concerned about the dangers to their international friends. They fear (no doubt correctly) that Maren and I, as well as their other friends and customers in the USA and elsewhere, are in far graver danger from the virus than they are.