SE Asian Tribal and Ritual Art: The Inevitability of Change

Older tribal and ritual artifacts – those dating from the mid-20th century and back – have nearly disappeared from the local markets. It’s not just a matter of prices inflating (and, in the robust, Chinese-fueled economy, they are), but the limited number of items originally created and used for ceremony that are still village-owned may be diminishing. A good example of this would be the wooden masks used in the Taoist ceremonies of the Yao (Yao-Mun subgroup) people of northern Vietnam and southern China.

When the region began to open to international business in the late 1970s following a generation of war and isolation, many of the older tribal artifacts were snapped up by international art and antique entrepreneurs and collectors. We’ve been told this is not a problem in itself for the Shaman and Taoist Priests; older, ritual items had their power ritually transferred to a new replacement – apparently, patina does not affect power. But much of the older, financially-valuable art was sold.

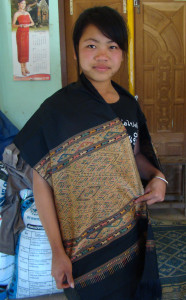

Our friend Phut (the “h” is silent), master-dyer and designer, modeling two of her shoulder cloths in her home. Notice the dichotomy between the turquoise Chinese refrigerator, plastic laundry basket, vinyl floor, and posters, and the traditional wooden stool with the hand- woven pillows and door curtain. This is one of the finest homes in Xam Tai.

Also, the mid-20th century hill-tribe elders were the last to be relatively unaffected by powerful global forces. Today the Yao and many other hill- tribe groups broadly support efforts to be literate and savvy in western ways. Like us, they yearn for their children get a good education and live healthy, productive lives. Refrigerators, motorcycles, eye-glasses, television, ice cream, medical clinics, Pepsi, power tools, political representation…. What’s not to like?

A Red Yao woman and children, with a mix of traditional and western clothing sit on Chinese plastic chairs next to the road.

This seductively convenient, modern world does not lend itself to investing time and talent into ritual protection and ceremony that supported a life that now, to many, may seem distant from modern realities. Three generations after Vietnam gained its independence, and two generations after a war killed millions and established a communist government eager to unify its people, the ancient village traditions that uphold the importance of certain beliefs are changing.

A young Lao man in western clothing playing pool with his friends while still wearing his hand-forged machete with a wooden hilt and handwoven rattan scabbard.

For those of us with our feet planted firmly in 21st century Western ways, a normal gut-reaction is to bewail what we might interpret as a loss of cultural innocence in an increasingly complex, competitive world. Indeed, many of these traditional hilltribe people are on the edge of a cultural precipice. How can the desire for health, comfort, stability and convenience be integrated into a world imbued with traditional beliefs? How can healing traditions maintain meaning in a world where Neosporin cures the infection?

The beauty, honesty, and expression inherent in the hilltribe people’s traditions inevitably must adapt to be meaningful in the modern world (as with Tai Daeng weaving), or else they will be buried in the sands of time as have our own ancestors’ ways