Welcome to Ban N——-: Treasured Secret of Houaphon

Nope. We won’t give you the precise location of the “X” on our treasure map; advertising remote, precious enclaves of talent and beauty eventually tears the “Shangri-” away from the “La.”

A day’s visit of this village begins in the Houaphon Province’s provincial capital, Xam Neua (population 35,000) where we rent a vehicle, driver, and for both purposes of business and pleasure, a translator. After a chatty hour on the twisty, paved one-lane “highway,” we veer onto a dirt path, splash through a shallow river and then drive for another hour or more. The single-track dirt lane follows a windy creek up a narrow, sparsely populated valley. Finally the narrow valley opens up to a wider set of verdant rice fields and this 50-house village.

We are fortunate that our 18-year-old translator’s parents live in Ban N—— – his status as a translator and “tourist guide” grant him a certain standing in the community, and his personal knowledge and contacts open a window that is unique for westerners. Good travelers aren’t bashful and we swing that window open, taking full advantage of his personal connections.

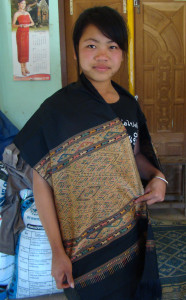

We take the first half-hour of our visit to wander through the muddy village, greeting the women, children, and a few older men (the young men were in the rice fields). Maren had remembered to bring photos of the weavers holding their artwork taken from our previous visit, and we suddenly get caught in the center of a flurry of women and children trying to see each photo as we connect the face in the photo with the face in the crowd. We also offer photos to the weavers of some Eugene-locals who had purchased their individual pieces. Every photo seems particularly entertaining, and everyone laughs and chats. Needless to say, we have no difficulty getting them to pose with their healing cloths on this visit, and I trust that they are looking forward to our return next month, new photos in hand.

Ban N—– looks similar to other Tai Daeng villages. Houses sit on wood posts 4-5 feet above ground; the walls are made of woven bamboo slats and wooden boards and the house’s interior are often divided by a curtain or flimsy bamboo panel into 2 or 3 rooms, allowing some privacy for sleeping. Each home has a pad of rock built into the floor, upon which the hearth is stoked and hot meals are prepared; if it is early morning or evening, smoke fills the upper rafters and finds its proper vent. Under each home, in the cooler shade, sits at least one bed-sized loom, often next to a wooden ox-cart, a builders’ stash of bamboo, or racks of drying corn. A woman more than likely sits on a wood bench flicking the loom’s shuttle back and forth and tying off colors of silk threads as she creates a traditional healing cloth. A packed dirt track, about 20 feet wide, runs down the center of the village.

We admire the half-woven shawls set on the looms under the houses, share a drink or two with the family and friends of our translator, and, after paying respect to his parents, are led to a community room – the village’s one building that is made of cement and not bamboo and wood. About two dozen weavers sit in a semi-circle in front of us, and in the center of the room are perhaps 60 healing cloths and other local textiles of all colors – from light lavender and peach pastels to dark red and rich golds. In Laos, individual villages often focus on developing a certain talent and status regarding that talent. We have visited villages that specialize in knife-making, basket-weaving, or shaman-cloth weaving (see Newsletter #2 about our visit to a weaving village, Muang V—, that specialized in shaman cloths). Ban N—–, for generations, has specialized in healing cloths, and their beautiful and near-flawless work, a stack of which sits before us, is renown in Laos.

Choosing the best for Above the Fray is never an easy task, especially given the wide variety of designs and colors. If there were no rules we would buy most everything – not only for the beauty of the art, but also for the smiles and hearts of the artists in the room. However, business and budgets interfere, and we embark on our routine of deliberate inspection. Some textiles, indeed, are more “flaw-free” than others, and some have more sophisticated and thoughtful color and design-play. Some have cruder edges; a common flaw is too-tight a pull on one side of the warp that produces, when ceremoniously displayed as wall-art, a decidedly banana-shaped textile (making it, perhaps, a beautiful shawl, but cattywampus wall art…).

We are looking expressly for the woven silks that have an inner “glow” – the cloths that hold all the elements together to create one precious unique expression that took generations to hone. From what we have seen as we visit other weaving villages and the major city markets in Luang Prabang and Vientiane, Laos’ capital, (where the majority of the village-made cloths eventually end up through a chain of distributors), no village weaves more profound, precise, and “glowing” healing cloths than Ban N——. After two hours of comparing, selecting, gently bargaining, photographing (thank you, Zall!), laughing, and completing our business, we pick up our armload of purchases, say goodbye for the umpteenth time, and, under a now-threatening sky, clamber back in the vehicle.

We discovered in Ban N—– that one of their finest young weavers, of whom we had a picture from the previous year, had just married and had moved to an unmapped village a few kilometers up the track. A half-hour later we found ourselves under a tin roof, during a sudden downpour, sharing photos and chatting with the beautiful, now-married young weaver and her proud husband. This village did not do as much weaving, but did they have some baskets! Another “X” on the map….

We still juggle in our minds the juxtaposition of what appears to be a poor, humble mountain village creating, under each home like a foundation, the most jaw-droppingly complex and color-savvy woven silk art. The heart of these fine people is not in their assets or their access to goods and services. The heart is rather tied to culture and tradition, their beliefs and their families, the providence of a tough land and the talents created from their minds and fingers.