Meet Chola & Her Family

It always happens. Just when we have maxed our budget for a village, someone else shows up with a beautiful textile.

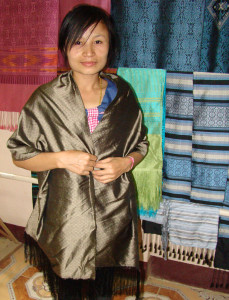

Chola modeling the butterfly scarves woven by her daughter that we bought the first time we met her.

We first met the woman we have nicknamed “the ghop lady” – the frog lady – on our second trip to her town in Houaphon Province in NE Laos. We had packed our gear and purchases, and were about to leave town to head to the border with Vietnam, hoping to cross and find a ride to Hanoi that same day if possible. We were sitting on the bench outside our guest house, putting on our shoes, when a woman showed up with some beautiful scarves. With our very last few kip (Laos money) we purchased four scarves from her; two with butterflies, and two with a very traditional flower pattern and stylized frogs, or “ghop” in the Lao language; thus her nickname.

We came back to her town on our next trip, having sold three of her four textiles, and looking for more. This time, we showed photos of her we’d taken the previous visit (and you thought this was only for our customers!) to people in the market, asking if she had a stall in the market or a home nearby. No one is a stranger in these small towns, and soon we were knocking on her door and calling “sabaidee”. Unfortunately, she was out of town, in the capital of Vientiane, selling her textiles to the market vendors – we had missed her!

On the next trip 6 months later, she was home and recognized us. She cheerfully invited us into her home where we were seated on handwoven floor-pillows, brought glasses of water, and a plate of local jicama and oranges to munch on while viewing textiles. While she went upstairs to get bags of textiles (literally – large plastic garbage can liners), her 8-year-old son sat shyly in the corner watching us. Chola put the fans on “high” to keep the sweating to a minimum (hah!), and we started unfolding her offerings: beautiful shawls, narrow scarves, and even some pieces she had made as part of her wedding linens (just to show off as these were not for sale!). One of her older pieces was a delicately woven mosquito net made of a silk patterned band as long as a bed is around from which handspun, handwoven, indigo-dyed cotton was suspended both across the top and down the sides to reach to the floor – this provides not only bug protection, but also privacy given that all family members traditionally sleep in one room. She also showed us a beautiful door curtain, hung in place of an inside house door, that was silk on cotton. She is keeping these pieces for herself, and maybe for her daughter to inherit. To see such treasured pieces is a treat!

One of the pieces she brought out of the bag was a door curtain with a repeated rat pattern. I fell in love with it and asked if she made it. She motioned to her son to come over, and said he had woven it when he was 7 years old. He was now embarrased to have woven it because, at the ripe old age of 8, he now thought of weaving as something women did, not boys. Despite his embarrasment, we took a photo of him displaying the piece. It is now one of my treasures! While we have found similar rat door curtains, this is the only one woven by him.

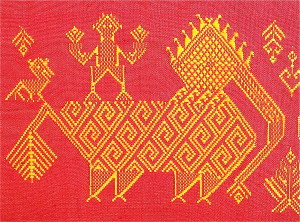

The following season when we visited, we found Chola and her daughter out on the cement patio in front of their home; her 14-year old daughter was weaving on one of the two looms set up under a metal roof. And the daughter was weaving those exact butterfly scarves! We indicated that we would like to buy some, and they meticulously unwrapped the already woven scarves and cut them off of the loom, the daughter beaming shyly, but proudly, the whole time. Zall (also 14!) took photos of the butterfly scarves coming off of the loom. The daughter also wove narrow scarves with love birds on them – we couldn’t resist those either!

The trip when Grandma came with us, we didn’t manage to visit until night was falling. Unfortunately, it was a night without electricity (not that uncommon in this region), and we made our selections by candlelight and flashlight! We often end up choosing textiles by the light of (I swear!) a 15 watt light bulb, but trying to make selections with a single candle’s glow was a new one even for us. Knowing the quality of the weaver’s goods makes a big difference under these circumstances. We did go back the next morning to pick up the scarves, as several of them needed to have the fringes braided. We also selected a couple more of her cheerful silks – the ones that haunted us overnight – all the while asking about the patterns and techniques. We have to acknowledge none of this conversation on this visit would have been possible without our good friend Mai, who grew up in Chola’s village but left after high school with a rare opportunity to attend college, learn English, and develop a professional career.

We usually have a translator with us on our visits to this village, but not always. Half of our conversations with Chola are a combination of sign language, Maren’s very limited Lao skills, a calculator, and constant laughter at our sometimes fruitless efforts to clearly communicate. The blend of translated and non-translated communication is part of what makes these relationships so fun!

Chola and her daughter are now regular artists represented by Above The Fray. We always visit her when we go to that village, and hope that she is there. We have tried to call her in advance, through a friend and translator, but her phone never seems to work. It is just the luck of the draw if she is there and has textiles for us. Part of the adventure!